Animal migrations are nothing sort of fascinating: the Arctic tern flies from the Arctic circle to the Antarctic, monarch butterflies travel the entire East Coast to end up in Mexico. Eels take a long journey, too: from the shores of Europe all the way to the Sargasso Sea, where they mate and give rise to their flat, clear-as-glass larvae. Or so we think. The truth is that no one has actually seen an eel mate in the wild.

Even from ancient times the origins of eels have puzzled us; where and how they reproduce is still unknown. Aristotle thought that they wriggled up from the soil when it rained. In ancient Egypt it was believed they spawned from sunlight soaking the shores of the Nile. Freud dissected hundreds of eels trying to discover their sex organs; he was unsuccessful and refused to acknowledge the research.

|

| Maybe they're just a little shy. |

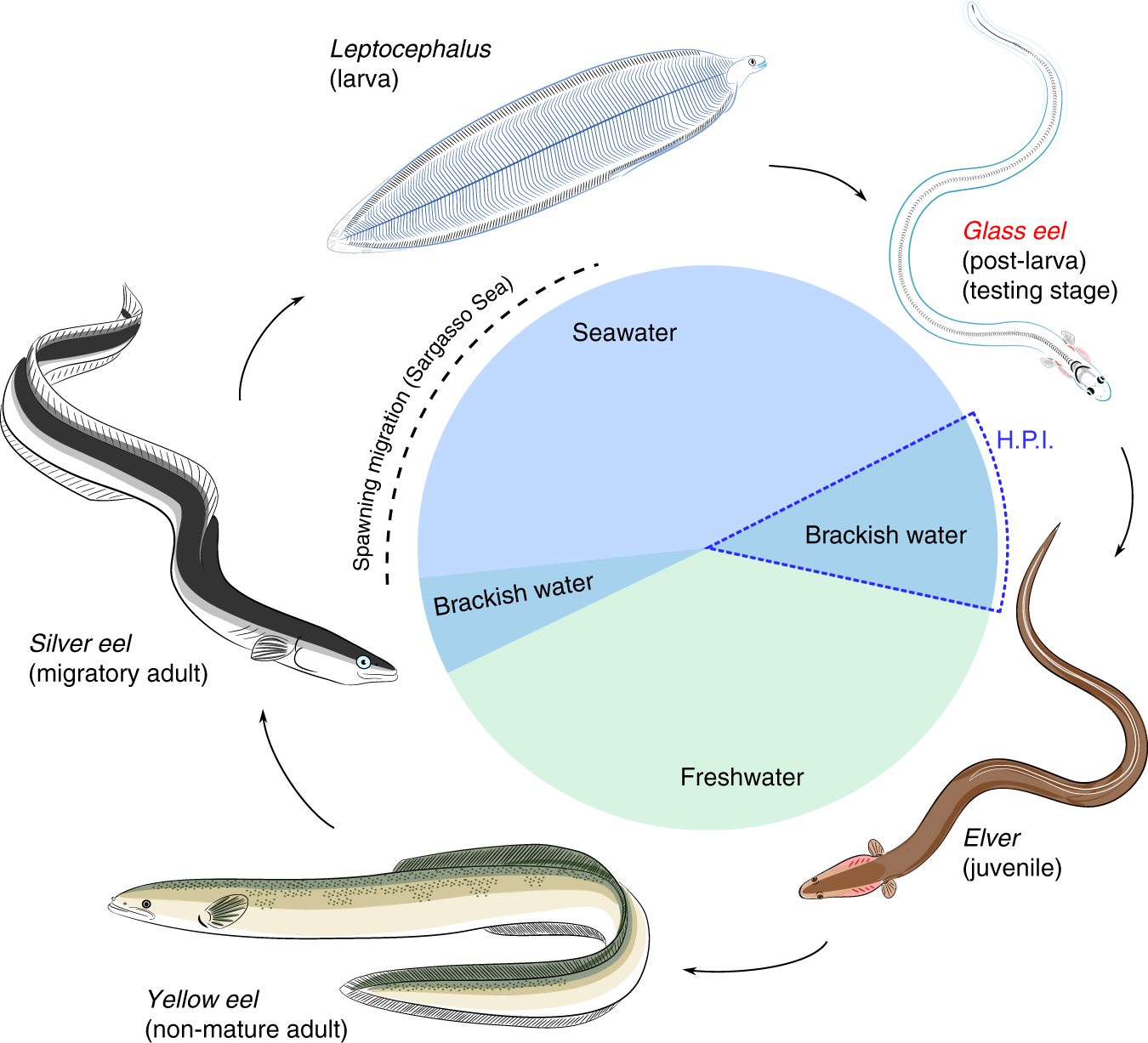

Today, we know that eels, specifically the European eel Anguilla anguilla, follow a predictable life pattern. They begin as flat, clear larvae, and mature into "glass eels", where they ride the Jet Stream to the coast of Europe. Once there, they migrate up the tiniest rivers and creeks, and then pull themselves onto land to colonize ponds and lakes. An eel on land can receive up to 50% of its oxygen from the air, making this journey less difficult than it sounds. Over the course of a decade, these young eels, or elvers, mature into the adult silver eels, and this is where their mating mystery begins.

|

| Eel life cycle. Leptocephalus larvae were once thought to be a completely separate species. |

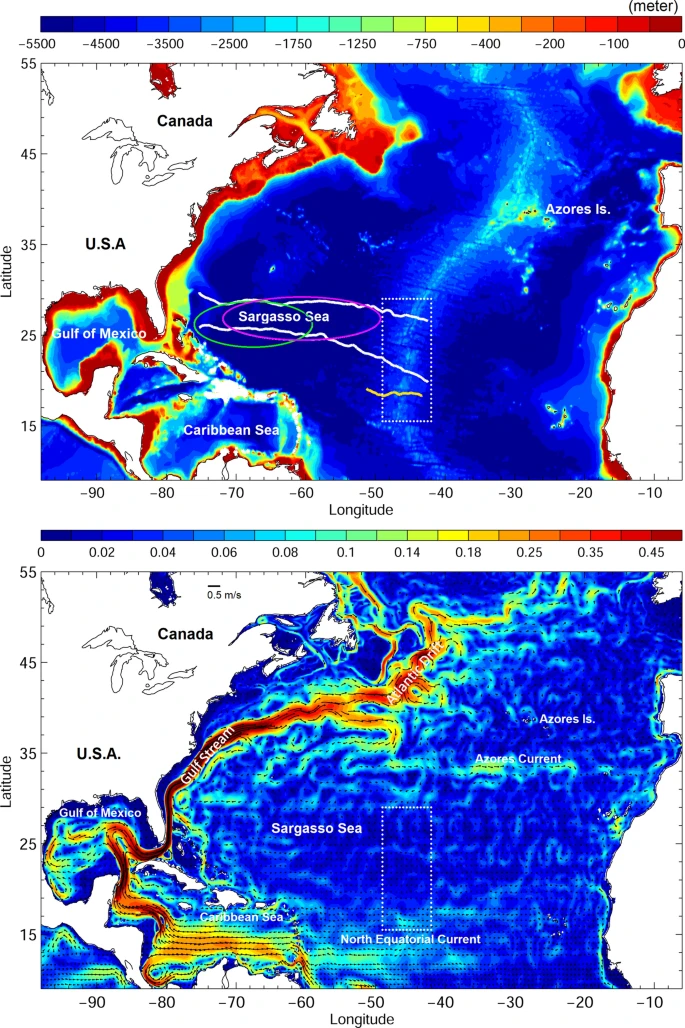

In the 20th century, Danish biologist Johannes Schmidt set out to track down the eel's origins. By capturing juvenile eels, he compared their sizes to see where the smallest and youngest eels were coming from, eventually pinpointing them to the Sargasso, that calm, shoreless sea near the Caribbean. But, though we have an idea where they spawn, no one has actually seen them do it. Eels have successfully reproduced in captivity, and, unlike Freud, we have located their sex organs. But the finer points are missing: no eggs or young larvae have ever been found.

A new hypothesis, published in 2020, aims to narrow down the area that European eels may be spawning in. With the Sargasso stretching 2 million square miles, the chances of two hot single eels meeting in the same area is slim (barring some kind of aquatic Tinder). Using virtual eel simulations based on earlier observations of the migrations, researchers proposed a new spawning hotspot along the mid-Atlantic ridge; more precisely, where this oceanic mountain range hits a salinity front, an area near the Azores islands, outside of the Sargasso. The cues of both the change in terrain and salinity could make this location much easier to find for mating eels. The Japanese eel, a related species, is known reliably to spawn at the intersection of a seamount ridge and a salinity front, adding credence to this theory. Manganese, a trace element associated with underwater volcanoes, was also found in high concentration in the bodies of European eels, but not in Sargasso sea larvae.

|

| "Green and magenta circles indicate areas where American and European eels have been observed, respectively8, and the white dotted box indicates the examined area for the numerical experiment." |

While eels were plentiful throughout Europe in the past, being a cheap food enjoyed by common people, today their populations have declined up to 90%, largely due to overfishing, parasites, and habitat loss. While it also solves a long-standing scientific mystery, discovering the mating habits of eels could also be a step towards keeping them alive.